Essential fatty acids, diet, and lifestyle factors influencing brain health, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease

- Dr. Radak

- May 15, 2021

- 65 min read

Updated: Jan 28

Omega 3, diet and lifestyle factors influencing brain health and risk for cognitive disease and impairment and relevance to vegan diets

By Dr. Radak - May 2021 (continually updated - last update September 2025)

As we age, the body naturally is susceptible to decreases in composition in many areas. For example, bone/bone mineral density steadily declines as we age and after attaining peak bone mass, we lose bone at about 3% per decade for cortical bone and 7–11% per decade for trabecular bone (O'Flaherty, 2000), and with some exceptions (i.e. menopause in women where it is even more accelerated), has been estimated to decline about ½ percent per year after age 50 (NASS, n.d.). Another example is the progressive loss of muscle tissue or lean body mass as we age, about 0.5% to 1.0% loss per year after age 70 (Siparsky, 2014). Most will also experience losses in vision and hearing as we age. Brain health and decline, as with other diseases, face a multitude of factors responsible for accelerating natural losses including genetics, overall diet, lifestyle factors, injury, diseases, and medicines, with diet and lifestyle factors playing major roles in preservation (Kahleova, 2021).

Brain weight or volume also decreases as a normal part of aging, estimated to be about 5% per decade after age 40 (Peters, 2006), and brain size/reserve is still a hypothesis being debated in relationship to Alzheimer's disease/Alzheimer’s-type dementia (AD) risk (Whitwell, 2010; An, 2016; Van Petten, 2004).

Dementia is a umbrella term that includes different types of dementia, including vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s (the latter of which makes up approximately 80% of all cases worldwide in those aged 65 or older (Reitz, 2014). Globally, an estimated 153 million people are expected to be living with AD by 2050 (GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators, 2022). In the US, the lifetime risk of dementia after age 55 years has been estimated to be 42% with the number of adults estimated to be affected from 514,000 to 1 million by year 2060 (Fang, 2025). It is a general belief that cognitive decline starts late in life, however most aspects of decline like memory, attention, and thinking occur in roughly the 20's and 30's (Salthouse, 2009; Statsenko, 2021) and some aspects like fluid intelligence may peak in the 40’s (Hartshorne, 2015) and as we age some processes are weakening while others are strengthening (such as dendrites expanding). The process may start even earlier as diet quality during pregnancy has been associated with brain health in offspring (Mou, 2024). While late-onset AD makes up the most cases (likelihood is about 3% at age 65, rising to over 30% by age 85) early onset AD can occur as well and is usually inherited (Sheppard, 2020). There are several underlying pathogenic mechanisms related to dementia: vascular endothelial damage, hyperlipidemia, inflammation and neuroinflammation, oxidative damage, impaired glucose regulation, and insulin resistance.

Research suggests that preserving brain size, especially the hippocampal region which is mostly composed of grey matter (GM) [but also white matter (WM)], can reduce risk for dementia (Virtanen, 2013; Zamroziewicz, 2017).

Lifestyle influences

The top modifiable dementia risk factor over that past decade has recently been overtaken, with obesity replacing physical inactivity as the leading risk factor (Slomski, 2022), though physical activity remains a major and significant modifiable factor. The benefits of physical activity are well established and compared to sedentary individuals, those who are physically active have a 30% reduction in mortality (Schnohr, 2015). The benefits for physical activity rank as one of the most significant modifiable factors and are consistently related to cognitive health and neurodegeneration, including positive effects in performance on neuropsychological tests, such as those involving processing speed, memory, and executive function and reducing risk for dementia and AD (USDHHS, 2018; Bangsbo, 2019). A meta-analysis of studies suggested that those with higher levels of physical activity were at a 38% lowered risk for cognitive decline while another meta-analysis found a 39% reduced risk for AD compared to those with little physical activity (Sofi, 2011; Beckett, 2015). Several mechanisms have been proposed for the strong beneficial effect physical activity has on brain health, including preventing degeneration, reducing oxidative stress, increasing neuroprotective factors and signaling pathways related to memory and learning, and increasing neurogenesis (Bartolotti, 2016). Physical activity favorably affects the level of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein in the brain and spinal cord that is involved in learning and memory (Mizoguchi, 2020). Even weekend warrior exercise bouts have been associated with less dementia and neurological diseases (Min, 2024).

Several lifestyle-related factors can increase risk and are modifiable. These 7 risk factors could result in being responsible for ½ of all AD cases: smoking, diabetes, midlife hypertension and obesity, depression, physical inactivity, cognitive inactivity (Farrer, 2001).

Sedentary behaviors like watching television, independent of physical inactivity has also been associated with increased risk for dementia (Raichlen, 2022). Conversely, the extent of cognitive complexity or utilization of brain function from factors like higher education, reading, writing or learning a second language are protective (Bartolotti, 2016), or even listening or playing music (Jaffa, 2025), all highlighting the importance of staying cognitively ‘active’. This also includes rigorous mental exercises, which have been shown to increase levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that naturally declines with age, and which in a clinical trial increased cognitive performance (Attarha, 2025). The Lancet Commission on dementia, prevention, intervention, and care recently added in 2024 two additional factors to their list of 12, visual loss and high LDL cholesterol, suggesting that addressing these 14 health and lifestyle factors may be able to prevent or delay 45% of dementia cases (Livingston, 2024). The Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention also suggests that 35% of dementia cases could be prevented by modifying nine risk factors: low education, midlife hearing loss, obesity, hypertension, late-life depression, smoking, physical inactivity, diabetes, and social isolation and collectively uses the acronym SHIELD to highlight these factors: Sleep, Head injury prevention, Exercise, Learning, and Diet (Montero-Odasso, 2020).

A 2019 review and others identified these factors: (Edwards, 2019; Ruan, 2018)

• Heart Disease (atherosclerosis major risk factor for AD (Janssen, 2014). Given that vascular problems affect not only the brain but also the heart, connecting both to disease, it is not surprising that clear and significant risks are also associated with cognitive decline/impairment and coronary heart disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation (Testai, 2024).

• Type 2 Diabetes (doubled risk for AD)

• Saturated Fat, Trans-Fat, Cholesterol, High fat diet

• Traumatic Brain injury

• Epilepsy

• Late Life Depression – for onset of AD

• Heavy drinking (and recent research suggests moderate drinking (Daviet, 2022)

• Sleep disturbances (30% increased risk for dementia for those with <6 hours sleep during middle age or for those with short sleep duration during old age (Sabia, 2021)

And it is not just the quantity of sleep needed, it is also quality. Almost 1 in 3 adults experience insomnia which is significantly related to increasing dementia risk, upwards of 51% (Wong, 2023; Marshall, 2024). Sleep quality in early midlife has also been suggested to predict brain age 15 years later, which is important given the association between brain aging and dementia (Biondo, 2022; Cavaillès, 2024).

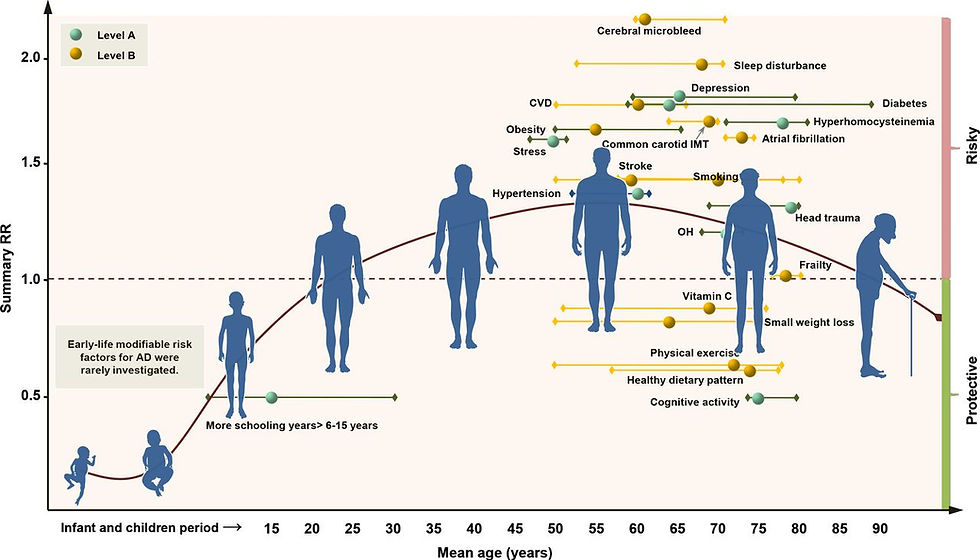

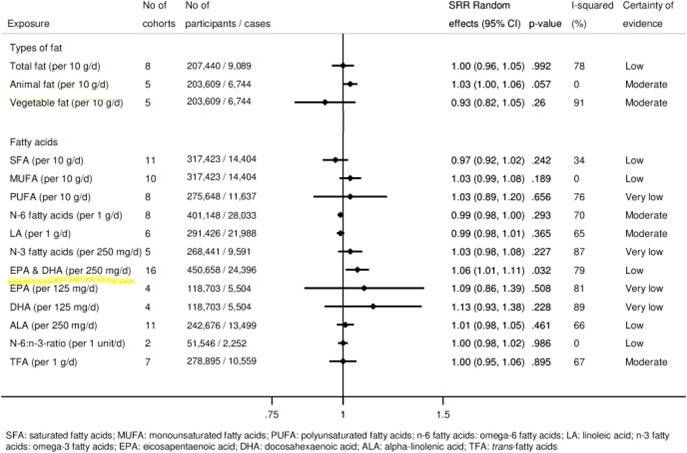

One of the largest reviews and meta-analysis of 243 observational studies and 153 trials found that the top 10 leading risk factors for preventing AD each receiving the strongest level of evidence were (education, cognitive activity, high body mass index in late life, hyper-homocysteinaemia (HHcy), depression, stress, diabetes, head trauma, hypertension in midlife and orthostatic hypotension) and little evidence for essential fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; 20:5ω-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 22:6ω-3), status or supplementation (Yu, 2020). The figure below highlights protective and risk factors that increase or decrease risk for AD.

Figure 5, Yu, 2020

The WHO Guidelines on risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia report highlights the importance of a healthy balanced diet and physical activity but also mention that as a strategy, polyunsaturated fatty acids are not recommended to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and/or dementia (WHO, 2019).

Most reviews did not cover the influence of loneliness, isolation, and lack of social connections on dementia risk. The vast majority of well-controlled studies suggest a significant increased risk for those being lonely, socially isolated or having poor social support or social networks (Penninkilampi, 2018; Huang, 2022; Salinas, 2022; Grullon, 2024; Luchetti, 2024).

On the flipside, positive lifestyle factors have been shown to reduce risk, delay and in some populations even prevent dementia (Yaffe, 2023), as well as extend life expectancy (Dhana, 2022). See the review by Barnard et al from the 2013 International Conference on Nutrition and the Brain or, Sherzai, 2019, or Yang, 2022 all highlighting the importance of healthy diet, physical activity, and sleep. Notice none of the reviews mention or express concern for Essential Fatty Acids or EPA/DHA as a leading risk factor.

Randomized controlled trials confirm that the strong effect lifestyle has on cognitive function. The 2 year long U.S. POINTER trial, demonstrated that healthy diet, physical activity and social and mental stimulation slowed the rate of cognitive decline (Baker, 2025).

The Tsimane and Moseten tribes in Amazon rainforest have some of the lowest incidence of AD and dementia in the world as well as less age-related brain atrophy and consume a predominantly complex carbohydrate low fat, low saturated fat diet (Gatz, 2022; Kraft, 2018; Irimia, 2021). The figure below highlights dementia prevalence and the low levels these tribes experience.

Gatz, 2022 - Figure 1

Nigeria also shares some of the lowest rates of AD despite having some of the highest genetic carriers of the APOE gene which makes the protein Apolipoprotein E, the highest genetic risk factor for AD, increasing risk by three and a half fold (Yamazaki, 2019). Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is the main protein responsible for cholesterol transfer in the brain as well as LDL cholesterol transfer within the body. The purported reason for the contradiction (known as The Nigerian Paradox) may be from the low levels of cholesterol and low intake of saturated fat and animal fat among Nigerians studied (Sepehrnia 1989).

Multiple nutrient factors at play

As Table 1 below indicates, various macro and micro nutrients are involved in neurodevelopment and later brain growth (Puri, 2023).

Puri, 2023 - Figure 1

Obesity and Trans Fatty Acids

Excess adipose tissue and its associated co-morbidities in middle-age has emerged as a significant risk factor for age-related cognitive decline (Vauzour, 2017), and obesity is related to brain structure deficits in older adults who are cognitively normal, those with mild cognitive impairment, and those with AD (Raji, 2014). Being overweight or obese in mid-life increases risk for late-onset dementia up to 2.44 fold (Dominguez, 2018). Inflammatory markers such as CRP or IL-6 are related to brain microstructural integrity and white matter lesions and ↑ risk for AD (Medawar, 2019).

While perhaps less of a concern as added sources of trans fatty acids are being phased out in the food supply, older adults who may of consumed trans fatty acids for long periods of time could be at additional risk. Older adults aged 60 or older in one study found that those with the highest levels had a 50% and 39% increased risk to develop dementia or AD (Honda, 2019).

Essential Fatty Acids and a focus on Omega 3 and 6 and Oxidation

Essential fatty acids are but one of many nutrients investigated in relation to brain health. Essential fatty acids, primarily Omega 3 and 6, constitute ~1/3 of total brain fatty acids mostly in the form of phospholipids of which docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) dominates for Omega 3 (trace amounts of α-Linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3ω-3) and EPA) and arachidonic acid (AA; 20:4, ω-6) (trace amounts of linoleic acid (LA) for Omega 6) (Cederholm, 2013; Luchtman, 2013).

These unsaturated fatty acids in the brain are highly susceptible to reactive oxygen species and lipid peroxidation (Albert, 2013) and when they are oxidized, increase harmful β-amyloid peptide, a hallmark of AD, and is one of several factors making the brain highly susceptible to free radical damage (Grimm, 2016; Nunomura, 2006). DHA is highly susceptible to oxidation, and lipid peroxidation in the CNS of AD patients is elevated (Long, 2008) and post modem studies in AD patients have elevated lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage (Lauer, 2022). It has been suggested that DHA may actually auto-oxidize and create lipid peroxidation in vivo resulting in oxidative stress (Grimm, 2016) and why nutritional supplementation of DHA, which may be prone to oxidation (as fish oil supplements contain oxidized lipids), while controversial (Ismail, 2012 ), may negate the benefits of DHA function in the brain as they could be prone to oxidation (Grimm, 2016; Mason, 2017) and produce harmful end products increasing risk for disease (Sottero, 2019; Kusumoto, 2023).

In general, DHA and AA have opposing effects on synaptic signal transduction and inflammatory signaling pathways (McNamara, 2017). However, arachidonic acid is equally important to brain health, development and maintenance as DHA (Gu, 2024) with both being tightly regulated and during pregnancy, gestation and just thereafter, has greater accumulation than DHA, and constitutes 20% of fatty acids in neuronal tissue, highlighting its importance and need to balance both AA and DHA (Hadley, 2016).

Brain size/volume

Studies investigating and correlating brain size or brain volume have primarily focused on EPA/DHA or just DHA. These studies mostly looked at either middle aged or older adults, and some who were very old, into their nineties. The aggregate of studies span a lengthy time period and should add confidence in understanding any long term relationship of Omega 3 fatty acids and brain health.

In primarily observational studies, regular fish consumption or fish oil supplements, or total Omega 3 intake or EPA/DHA status was associated (mostly via MRI scans of the brain) with preservation of either brain size, grey matter (GM), white matter (WM), medial temporal lobe (mtl), cortical thickness, lower white matter hyperintensities (WMH), which are associated with cognitive impairment/dementia. (Bowman, 2012; Tan, 2012; Virtanen, 2013; Walhovd, 2014; Daiello, 2015[1]; Zamroziewicz, 2018; Thomas, 2020). Some of these studies such as Daiello, 2015[1], did not factor or investigate any lifestyle or dietary data (including fish consumption) other than fish oil supplementation.

Other studies showed no or mixed association either via assessing blood DHA status or dietary intake, and one study suggested benefit from marine Omega 3’s that was attenuated when controlling for depression (Ammann, 2013; Samieri, 2012; Raji, 2014; Pottala, 2014; McNamara,2018; Bowman, 2012; Bowman, 2013; Conklin, 2007; Luciano, 2017; Titova, 2013; Loong, 2024). A few examples of mixed or conflicting outcomes:

•Virtanen, 2013 found no association with markers of brain atrophy for blood EPA,DPA, or DHA (there was benefit for DHA for risk of subclinical infarcts (brain lesions) during the first MRI, but not in-between the second MRI.

•Raji, 2014 found a positive association with fish intake, blood levels of EPA/DHA and grey matter volume, however there was no association between blood EPA/DHA and grey matter volume.

•In evaluating the Mediterranean diet, Luciano et al., 2017 found in their study of 400 older individuals, a beneficial effect in preserving brain volume with the diet, however fish did not drive this beneficial effect.

•Titova, 2013 found that in older female cognitively intact adults, greater self-reported EPA/DHA intake was associated with better global grey matter volume 5 years later and with cognitive tests, but not global white matter or total brain volume or regional grey matter volume. When analyzed by adjusting for cardiometabolic confounders, the association became non-significant. When plasma EPA/DHA was evaluated, no association was found for any aspect of brain volume or cognitive testing.

•Bowman, 2013 found that in older cognitively intact adults with mean age of 86 and followed for 4 years found that via MRI scans blood EPA/DHA was associated with less executive decline and more stable executive function over time but no association with memory function or global cognitive changes. The benefit of EPA/DHA became non significant when factoring in total white matter hyperintensity volume.

•Conklin, 2007 found intakes of EPA/DHA were correlated with increases in grey matter volume, but when evaluated via the whole brain, no relationships were found with EPA/DHA.

•Pottala, 2014 found that in adjusted models, higher omega-3 index in postmenopausal women was correlated with larger total normal brain volume, but EPA and DHA were not associated with total brain volume, and a higher omega-3 index was correlated with larger hippocampal volume. In bi-variate analysis, neither the omega-3 index, EPA or DHA was associated with brain volume and the authors noted that the omega-3 index can be confounded by a number of factors such as education, physical activity, body mass index, CRP, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides

•Samieri, 2012 found that blood levels of EPA but not DHA in older adults was correlated with less atrophy of the right hippocampal/parahippocampal area and of the right amygdale regions.

•Ammann, 2013 found that the omega-3 index was not correlated with any aspect of cognitive decline.

Reviews have also been mixed, with one finding support (Cutuli, 2017) while another more recent review indicated results are inconclusive (Macaron, 2021). The review by Macaron investigated 12 available studies (8 cross-sectional, 3 observational, 1 trial) looking at omega-3 and brain morphology and volume in cognitively intact older adults. Findings were inconsistent and authors concluded that “Current evidence is still insufficient to formulate recommendations for omega-3 intake to support brain health specifically“.

Cognitive impairment or decline/Alzheimer Disease - Seafood & DHA

Observational studies on fish intake and risk for mild cognitive impairment or decline are conflicting in short term studies (Zhang, 2016, Wu, 2015; Beydoun, 2007; Roberts, 2010; Solfrizzi, 2017). One study also found higher DHA levels to be associated with slower learning performance in non-pregnant healthy women (de Groot, 2007). Fish intake has also been associated with subclinical neurobehavioral abnormalities (Carta, 2003), and the authors attributed 60% of this result to mercury blood concentrations.

A sizable number of studies suggest reduced risk for dementia or AD either for fish intake or high omega fatty acid status levels though some are conflicting with no improvement (Raji, 2014; Zhang, 2016; Cole, 2009; Alsumari, 2019; Cunnane, 2012; Lukaschek, 2016; Sala-Vila, 2022; Godos, 2024). Some showed improvement in mental scores but no reduction for probable dementia or cognitive impairment (Ammann, 2017). Some considered fish intake only, with no other dietary factor included.

An example of mixed outcomes:

In a sample of Adventist Health Study-2 participants, 40 cognitively healthy individuals were evaluated for brain volume, cognition and Omega 3 fatty acids. EPA, DHA, and Omega 3 Index were all correlated with white matter volume. However, none of the omega-3 FA variables were correlated with the hippocampal volume or the frontal pole cortical thickness, and EPA and the omega 3 index but not DHA were associated with the Entorhinal Cortex. Among the 6 cognitive tests, DHA had no association to any, while EPA and the Omega 3 index were associated with only 2 of the tests. The authors noted they expected stronger results given the positive research surrounding omega 3 fatty acids and brain health. Note that diet categories, physical activity and several other important factors relating to brain health were not assessed or controlled for (Loong, 2023).

Other research found high fish intake to worsen cognitive test performance in older adults as well as fish consumption in childhood predicting worse cognitive performance later in life (Danthiir, 2014). Some longer term studies (i.e. 10 years) found no or minimal association between fish intake and long term risk of dementia. For example, the Rotterdam Study looked at over 5000 elderly with moderate fish intakes and did not find an association with dementia nor AD at various levels of fish intake compared to those with no fish intake. This was their second study (10 years in duration) as their first study (just 2 years follow up) used the same data and had showed fish intake was helpful, though not for total omega 3 levels (Devore, 2009).

Other observational studies looking at healthy older adults who habitually consumed fish oil supplements found benefit for dementia but not for actual AD (Huang, 2022). This study did control for some lifestyle factors but other than dietary supplement, diet was not included and could be a confounder as mentioned below.

Some studies did not control for trans-fat, fruit and vegetable intake, ultra-processed foods, diet sodas or sugar sweetened beverages, blood glucose, physical activity/exercise, all of which are associated with cognition or AD risk, some very strongly so. Other areas that may not of been investigated or controlled for include coffee, green tea or caffeine consumption which has a neuroprotective effect against cognitive impairment (Liu, 2016; Zhu, 2024) possibly due to caffeine acting to block adenosine receptors in the nervous system (Chen, 2020). Nor for artificially sweetened sodas or sugar sweetened beverages which significantly and dramatically increased risk for all-cause dementia or AD (Pace, 2017; Frausto, 2021; Gonçalves, 2025). One diet soda per day was linked to almost a three-fold increase risk for dementia (Pace, 2017). Nor for Bisphenol A, one of the most produced synthetic compounds in the world which has been used in can and bottle linings and food storage containers for decades and has been implicated in AD pathology and the development and progression of neurologic disorders due to its neurotoxic effects (Suresh, 2022; Suresh, 2024; Costa, 2024). Nor for medications that are associated with brain atrophy (Raji, 2014; Walsh, 2018), or for hypertension, which can predict both vascular dementia and AD 20 years before onset (Janssen, 2014) or other nutrients (including AA), high sodium intake which is associated with increasing risk for dementia and AD (Mohan, 2020; Chen, 2025) or even High HDL cholesterol levels (Hussain, 2023) that have an association with dementia risk. A systematic review of 130 million individuals found an increased risk for dementia or AD associated with diabetes drugs, and antipsychotics, while finding a reduced risk for antimicrobial drugs, anti-inflammatory drugs, and certain vaccinations (Underwood, 2025). Nor for social contact and isolation, which is a risk factor for AD and dementia (Hirabayashi, 2023). Even habitually skipping breakfast has been found to increase the rate of cognitive decline as well as increase biomarkers of neurodegeneration (Zhang, 2024).

This is hugely problematic yet these largely are not controlled for in research! Most of these studies pay no or incomplete attention to diet or other lifestyle factors and focus exclusively on red blood cell levels of DHA or EPA/DHA and the outcome of AD and usually do a single point in time sample which may not be a good measure of predicting long term risk for AD. To provide an example of how these studies report their research looking at the Sala-Vila, 2022 study (of which one of the authors has stock in a company providing omega 3 testing): They usually create 4 quintiles from lowest (Q1) to highest (Q4) and show reduced risk in Q4 for those with the highest DHA or EPA/DHA. To explain just one reason why this may not be meaningful: those in Q4 could have DHA or EPA/DHA levels simply as a marker for a healthy diet (switching from meat to fish) and overall healthy lifestyle. Markers for a healthy diet are well known. For example, those who drink more water tend to eat more fruits and vegetables, whole grains, less refined grains, and more seafood (Leung, 2018).

Many of these studies occurred during a time when the public was being informed to reduce meat intake and make other healthy lifestyle recommendations to reduce cardiovascular disease. And given how many factors are associated with AD risk, this is very important, and as mentioned not accounted for in these studies. Also, those placed in Q1 may be high meat consumers which could have very poor diets overall, low seafood, and consequently low EPA/DHA. Their study conclusions are DHA is helpful to reduce AD risk. A significant amount of research has shown that nutritional status, particularly poor diet or malnutrition negatively impacts cognition and cognitive performance, accelerating cognitive decline, and therefore is important to recognize the context of 'low Omega 3' status concurrent with poor nutritional status (Macaron, 2021; Sanders, 2018). An example of why other dietary factors need to be controlled for comes from a study looking at those with and without AD. This study looked at plasma lipids, finding lower poly unsaturated fatty acids in women with AD, but they also found higher saturated fatty acids as well (Wretlind, 2025), highlighting the need to look at more than just Omega 3 fatty acids when making associations. Another dietary factor, often uncontrolled for is alcohol. While previously, it was believed that moderate alcohol intake was protective, several studies suggest any amount of alcohol increases risk for dementia (Topiwala, 2025).

Despite the inconsistency in the research, as DHA plays an important role in the brain and has been the main fatty acid of interest, could vegans who typically (but not always) show lower DHA status be at some additional risk?

To explore this further, what follows is a review on some of the research surrounding this topic. Both individual nutrients and dietary patterns will be reviewed.

Firstly, the above observational studies may suffer from self reported dietary information, use of only a single measurement, possible residual confounding due to not adjusting for numerous risk factors and being mostly cross-sectional studies (which do not permit conclusions on causality). These weaknesses are similar to observational studies looking at Omega 3/DHA and cardiovascular disease. Some also used small sample sizes. See the section below on ↑↓ Brain size/volume for the many factors influencing brain size that may not have been controlled for in these observational studies.

We don’t consume an individual nutrient or even protein group (like solely fish) in our overall diet, and it is possible that DHA may just be a marker of a healthier lifestyle. Those following healthier diets (for example those replacing meat for fish) tend to be more physically active, smoke less, and have lower body mass index (Solfrizzi, 2017). Higher fish intake may also be associated with higher socioeconomic status which is protective for AD and cognitive decline (Alsumari, 2019; Sattler, 2012). Many of these studies occurred during a time when recommendations were made to reduce meat intake and replace it with healthier options such as fish, which may indicate that EPA/DHA status was a marker for a diet healthier than a meat-based diet. Meat is typically a greater source of saturated fat than fish i.e. same portion of ground beef to salmon fillet has 4.5 and .73 grams, respectively)

Other dietary hazards within meat, such AA (which competes with DHA in the brain), cholesterol, and saturated fat may have been reduced/replaced by fish/seafood as part of a healthier dietary change (which often includes increased exercise, which, by itself is a significant contributor to brain health; even just 10 minutes daily during mid-life (Palta, 2021). Meat has one of the strongest correlations with AD prevalence and dementia risk, likely due to hazards like increasing inflammation, insulin resistance, oxidative stress, saturated fat levels, advanced glycation end products, homocysteine levels, and trimethylamine N-oxide (Grant, 2023; Katonova, 2022). Low consumption of meat and meat products has been linked to a better cognitive function, though not in all studies (Zhang, 2020) and also greater total brain volume (Titova, 2013) and processed meat intake (a Group 1 carcinogen by the WHO) is positively associated with dementia (Zhang, 2021). In the Nurses' Health Study (NHS) and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), a total of 133,771 participants followed for up to 43 years , long term processed red meat intake was significantly associated with dementia as well as accelerated aging in global cognition, with 1.61 years of additional aging per serving, compared to those who ate little to no processed red meat (li, 2025). Unprocessed meat did not increase dementia but did increase subjective cognitive decline. The lead author explains that “Red meat is high in saturated fat and has been shown in previous studies to increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease, which are both linked to reduced brain health”.

Why is saturated fat and cholesterol important? A recent meta-analysis of cohort studies suggested a strong effect for higher saturated fat intake which was associated with a 39% and 105% increased risk for AD and dementia respectively and no association was found for polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), which includes Omega 3 and 6, for either AD or dementia (Ruan, 2018). Cholesterol levels are higher in those with AD than those without, and hypercholesterolemia is a known risk factor for AD as well as severity of AD (Roher, 2011; Wu, 2022). One explanation could be fat and cholesterol creating atherosclerotic plaque in cerebral arteries as autopsies comparing those with or without AD showed major clogged cerebral arteries among AD subjects whereas other studies showed increasing clogging of brain arteries from mild cognitive impairment to AD (Lathe, 2014; Zhu, 2014).

Both saturated fat and cholesterol are modifiable dietary risk factors. LDL cholesterol levels are also important. A large study involving 100,000 matched pairs found low LDL-cholesterol levels (<70 mg/Dl) to significantly reduce risk for dementia (Lin, 2025). Further, oxidized cholesterol can be many times more toxic than regular cholesterol, with oxidized cholesterol in the form of oxysterols promoting neuroinflammation, and has been shown to increase risk for cognitive impairment and AD (Liu, 2016; Wang, 2016). Direct sources of oxidized cholesterol through the diet are found in animal products like meat, fish, eggs and cheese (Lordan, 2009).

Additionally, some disease states linked with dementia or AD may not have been controlled for in these studies. Other influences besides disease may not have been controlled for. For example, pesticide exposure has been linked with cognitive function (Dardiotis, 2019), with common household insecticides and agricultural pesticides being significantly associated with cognitive decline in older adults (Kim, 2021). Air pollution has been significantly associated with increasing risk for dementia with prolonged exposure also increasing risk for AD and may increase inflammation and oxidative stress damage to the brain (Bartolotti, 2016; Parra, 2022; Zhang, 2023).

While aluminum has not been shown to cause AD, there has been some association in some population groups (Kawahara, 2011), it has been shown to be in higher levels in the brain of AD patients who have a familial AD (Mold, 2020), and a study looking at fluoride and aluminum in drinking water found a dose response increased risk for dementia, renewing the established debate for implicating aluminum (Ross, 2019). Another study found DNA damage to be associated with aluminum (Celik, 2012), another found significant pro-oxidation and free radical damage with aluminum levels in the blood (Celik, 2012), with an estimated 20% of our daily intake of aluminum coming from cookware (Celik, 2012) and confounders like these are almost never considered in these studies. An excellent review on aluminum by Dr. McDougall is here. All of these possible factors may dilute the strength of the findings.

The other concern with studies that show an association with DHA and brain health is the reductionist style of isolating DHA and interpreting it as the sole reason for the association. As Solfrizzi et. al, 2017 state "There was also accumulating evidence that combinations of foods and nutrients into certain patterns may act synergistically to provide stronger health effects than those conferred by their individual dietary components." Dietary intake of seafood may provide other nutrients related to brain health beyond EPA/DHA potentially confounding associations between DHA and brain health. Fish contains Vit A, D, B-12 and B-complex vitamins, Mg, iron, iodine, selenium, zinc, and has lower saturated fat and cholesterol than meat, the underlined items of which are related +/- to cognitive decline or AD risk (Raji, 2014; Annweile 2016; Andrási, 2009; Berti, 2015; Dominguez, 2018; Medawar, 2019; Varikasuvu, 2019). Some studies did not take into account any dietary nutrients, especially the aforementioned.

It is also unclear if low DHA (found in some but not all post mortem brain studies) is a cause or consequence of AD (Pan, 2015) or other factors. Cunnane (2013) suggest that it is puzzling that, if low DHA status or low fish intake is associated with AD, why post-mortem studies do not consistently show lower brain DHA (Fraser, 2010).

DHA in the blood and tissue – Relevance of DHA in Red blood cells

Most studies correlate brain health or disease risk with levels of DHA in the blood or plasma as tissue status is more complicated to assess; however, levels in the blood may not reflect the composition in the brain/CNS (Dyall, 2015). This is similar to many other nutrients, such as Magnesium, where serum levels do not reflect whole body content (Razzaque, 2018). A recent clinical trial investigated just how much DHA taken in supplement form reaches the brain by administering 2152mg of DHA or placebo along with Vitamin B complex vitamins for 6 months. Blood levels were significantly raised while modest increases in DHA were found with large intake of DHA suggesting blood levels are not a useful indicator for reflecting brain DHA levels. (Arellanes, 2020).

Plasma may be a good indicator of dietary DHA intakes though studies calculating percent DHA in esterified blood lipids may not be available to the brain for uptake, but instead plasma unesterified stores mediated by adipose stores may be sufficient for brain needs and uptake (Domenichiello, 2015). A study found essential fatty acids, including EPA and DHA were significantly released as unesterified fatty acids into the plasma free fatty acid pool from adipose tissue after an overnight fast (Halliwell, 1996).

It has been suggested that adipose tissue acts as a long term depot of DHA for the brain (Health, 2021). Adults are estimated to store in adipose 20-50g of unesterified DHA and 60-70g in whole body fat and estimates are that the brain DHA uptake rate is 3.8 mg/day suggesting that adult human adipose contains enough DHA to supply the brain for 14–36 years not taking into account other body needs for DHA. (Domenichiello, 2015; Luxwolda, 2014). And with ALA intakes at roughly the estimated adequate intake level, this would equate to a under< 1% conversion rate (0.14–0.22% ). So Domenichiello, 2015 suggests that even a small amount of DHA synthesis may be adequate for the brain.

Newer studies in vegans (Miles, 2019) indicated storage of DHA in adipose tissue despite no direct dietary source of DHA. Studies in vegans who obtain no pre-formed DHA are able to convert necessary amounts (despite being lower than omnivores) and with neurological disease rates comparable to omnivores (Domenichiello, 2015). Dietary DHA may also down-regulate DHA synthesis in the liver (where DHA becomes available to transported by lipoproteins and stored in adipose for uptake by the brain (Metherel, 2024). Some research has also questioned whether new analysis methods are needed. Domenichiello et al (2015) suggest that DHA synthesis capacity may be underestimated and question whether new analysis methods are needed, such as the steady-state infusion method. Such that, if measuring DHA uptake based on what level of DHA is being used in the brain, then estimates may be far less than predicted to maintain adequate brain health.

Some studies only used a single measurement of plasma or red blood cell (RBC) DHA. Although possibly stable over time, DHA levels do change and such changes may have biased the results in studies. Pottela et al (2014), for example, used a blood sample and then analyzed MRI scans 8 years later and suggested greater brain volume preservation with higher DHA status. The assessment was in one point in time and DHA in RBC may just reflect short term dietary intake and not what is reflected in tissue. And regarding dietary intake, this study obtained no dietary information for any of the three models used in the study, and as mentioned below, several nutritional factors can affect brain volume/size and were not accounted for in the study.

That study also compared those with low and high DHA status categorized by quartiles which represented brain volume. Though this did not reach statistical significance, the Q1 subjects had more disease prevalence than those in Q4 and may have influenced results. It was also unknown what the Omega 6 intake/status was as no nutritional information was analyzed. Perhaps, those in Q1 may have had higher Omega 6 status which could of influenced brain size?

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS), a prospective cohort study of 5888 older adults, assessed using brain MRI scans in relationship to plasma phospholipid Omega‐3 levels and dietary intakes and found benefit with increased plasma levels of DHA and less white matter abnormalities, but not for improvement in markers that indicate less brain atrophy. However, two findings suggest benefit for ALA: plasma phospholipid ALA was associated with improvement in markers that indicate brain atrophy, and dietary ALA was associated with less white matter abnormalities (Virtanen, 2013).

The study also found that frequency of fish consumption did not correlate with mental score testing but did show fish intake correlates with higher GM volumes in the brain areas responsible for memory and cognition, but conversely omega 3 status in phospholipids was not related to higher GM volumes. These results lead the authors to suggest that dietary intake of fish is not necessarily the presumed biological factor that can affect the structural integrity of the brain and there are other lifestyle reasons. And that fish intake may be a marker of a healthier overall diet or something else contained in fish like selenium content (Raji, 2014). The authors say this is consistent with Omega 3 supplement studies which show little effect on prevention of dementia or cognition in AD patients.

Supplementation Trials - Dementia or AD or Cognition

These trials using long chain Omega 3 supplements showed mixed or inconclusive results on cognitive performance or decline in youth and healthy adults or adults with dementia or AD (Cederholm, 2013; Raji, 2014; Daiello, 2015; Morris, 2016; Luchtman, 2013; Abubakari, 2014; Danthiir, 2018;Phillips, 2015; Jiao, 2014; Lin, 2022), or any positive effect on cognitive decline in healthy older individuals (Cochrane meta-analysis) (Sydenham, 2012; Dominguez, 2018). A Cochrane review of trials in those with AD or dementia also found little benefit for AD or dementia (Burckhardt, 2016). Nor did they benefit coronary disease patients (Geleijnse, 2012). There was a possible positive effect in those with very mild cognitive impairment (Daiello, 2015; de Souza Fernandes, 2015), and some benefit for some memory indicators in young healthy adults who had low DHA status (Stonehouse, 2013). One study showed worse memory using Algae DHA (Benton, 2013), while another showed a protective effect in those with minor memory problems for some but not for other memory domains and a protective effect in those with no memory problems (Yurko-Mauro, 2015).

In the largest and one of the longest double-masked randomized clinical trials yet (National Institute of Health AREDS2 study), lasting 5 years, >3500 participants who were at risk for developing late age-related macular degeneration were enrolled in a secondary cognitive study and given cognitive function testing: fish-oil supplements had no change in cognitive function compared to placebo and failed to reduce cognitive decline (Chew, 2015).

A long term well controlled trial in older adults with sub-optimal omega 3 fatty acid status used high dose 975 mg EPA, 650 mg DHA daily for three years, and failed to show any significant change in white matter lesion accumulation nor for neuronal integrity breakdown except those who were APOE*E4 carriers for a reduction in neuronal integrity breakdown. As a result, this may suggest limited benefit to exogenous EPA/DHA and also suggest plasma status of these omega 3 fatty acids may not be a useful marker for brain health (Shinto, 2024).

Two systematic reviews and meta analysis of RCT that showed no beneficial effect from fish oil supplements (Brainard, 2020; Balachandar, 2020).

Some suggest the reason for DHA supplements not being effective in AD is possibly the other nutrients in fish not contained in fish oil, many of which have an established association with brain function (Cunnane, 2013).

Only one study (Witte, 2014) using DHA supplements in a randomized trial which suggested an increase in GM volume and some (but not all) cognitive functions compared to a control group. However, this study had several methodological concerns which are detailed in my presentation and it is interesting that 7 years later, no study has replicated these results. Numerous non-DHA factors directly ↑↓ brain size/volume and were not controlled for in this study. See slides 29-34 for a detailed account of those concerns.

Randomized clinical trials using high dose Algae DHA, (up to 2g per day) for up to18 months were mixed with one finding benefit while another did not improve cognitive function, brain volume or rate of atrophy (Quinn, 2010; Zhang, 2017).

Short and Long Term studies

Dementia and AD is not a process that develops quickly, similar to other chronic diseases. That does not mean short term studies have no value, and certainly long term studies are not the only way to base decisions on risk factors for brain health. For example, short term studies like trials have been valuable in showing increases in brain volume with specific interventions.

Other fatty acids

While not a long term study, the research by Zamroziewicz et al (2017) on fluid intelligence and underlying GM structure found that ALA and downstream products like stearidonic acid (SDA) and eicosatrienoic acid (ETA) (but not EPA or DHA) were linked to fluid intelligence and preservation of total GM volume of the left frontoparietal cortex (FPC) which fully mediated the relationship between the omega-3 PUFA pattern and fluid intelligence. The authors suggest dietary consumption of precursor omega 3 may support neuronal health through the unique neuroprotective benefits of ALA and its immediate downstream products (Zamroziewicz, 2018). This was also suggested in another study where not only ALA but several other fatty acids, including Omega 6, were related to memory function and white matter microstructure suggesting that both Omega 3 and 6 may slow age-related decline and memory (Zamroziewicz, 2017; Berti, 2015). In a study investigating nutrient biomarkers and profiles and healthy brain aging, ALA and EPA, but not DHA were associated with delayed brain aging. Interestingly, two Omega 6 fatty acids were also associated with delayed brain aging, Docosadienoic Acid and Eicosadienoic Acid. These Omega 6 fatty acids have anti-inflammation and antioxidant properties meeting or exceeding that of DHA (Zwilling, 2024). Thus, while most researchers frame Omega 3 fatty acids and anti-inflammatory, and Omega 6 fatty acids as inflammatory, this is not the case, and that standpoint is relevant when considering EPA/DHA and AA. For example, a review of 15 trials mainly investigating LA found that none of the studies were related to increasing inflammatory markers (Johnson, 2012), which make sense as little LA is converted to AA (Rett, 2011).

Intakes of ALA are generally sufficient to convert to EPA (Domenichiello, 2015; Williams, 2006) and Saunders, 2013 suggest that when EPA or DHA intakes are low, the conversion of these from ALA may be increased to allow for maintaining higher tissue stores. This may be why ALA converts to EPA reasonably well and converts to DHA almost entirely in the liver, brain and fat tissues, to intentionally keep DHA out of the bloodstream to prevent negative impacts on vascular health. However, one long term trial lasting 9 months showed increases in DHA from adding 3 grams of flaxseed oil in all dietary groups investigated, including vegetarians and vegans (Klein, 2025).Some research suggested that some conversion of ALA to DHA may actually occur in the brain itself as opposed to primarily in the liver, making blood level assessments possibly subjective. A study in infants suggested DHA status in red blood cells only explained about ¼ of the variance in overall brain growth (Lauritzen, 2001). This may suggest that blood fatty acid tests and the Omega 3 index (which measures the percent of EPA and DHA in erythrocyte membrane lipids) are not representative of tissue stores or brain health.

A review of trials and observational studies suggest that alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) lowered the risk of CVD (10%) and CVD mortality (20%) and as CVD increases risk for AD, this could provide additional support for the importance of ALA (Sala-Vila, 2022; Bleckwenn, 2017).

Arachidonic acid (AA), which is the 2nd most prevalent PUFA in the brain and 20% of fatty acids in neuronal tissue, is considered an underappreciated risk factor for cognition/AD. AA produces PGH2 eicosanoids which are neuro-inflammatory which is why non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been shown to reduce risk for AD (Thomas, 2016). In AD patients, ↑ AA incorporation occurred via PET scan compared to healthy controls (Rapoport, 2008). Chicken and egg product intake represent almost 1/2 of AA from food sources in the US diet (National Cancer Institute, 2019). See Table 12 below. A two week long study suggested improved mood scores when restricting meat, fish, and poultry from the test diets with the authors suggesting these foods may negatively impact brain health (Beezhold, 2012).

National Cancer Institute. “Identification of Top Food Sources of Various Dietary Components.”

Non DHA Factors

Numerous non-DHA factors directly ↑↓ brain size/volume and most are modifiable.

↑↓ Brain size/volume:

↑:

exercise (Edwards, 2019; Jackson, 2016; Raji, 2024)

Mediterranean-type diet (but not fish in this diet) (Luciano, 2017)

higher diet quality during pregnancy (Mou, 2024)

fruit and vegetable/nut/whole grain intake (Croll, 2018; Gaudio, 2023)

magnesium intake (Alateeq, 2023)

meditation (Dodich, 2019)

↓:

chronic life stress (Gianaros, 2007)

obesity (Raji, 2014)

traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors (Song, 2020)

trans fat (Bowman, 2012)

Vitamin B12 and also homocysteine levels (Hooshmand, 2016; Spence, 2016)

higher blood glucose level in the normal range (e.g. 5.5 mmol/L versus 5.0 mmol/L) (Walsh, 2018)

sodium intake (Chen, 2025)

low levels of social contact and isolation (Hirabayashi, 2023)

meat and meat products (Titova, 2013)

moderate drinking (even as low as 1 drink/day) had a negative effect on grey matter volume and white matter volume, with additional negative effects in those who regularly consume several alcoholic drinks per day (Daviet, 2022)

Exercise training can also reduce brain shrinkage and improve memory as a clinical trial demonstrated in 120 older adults over a 1 year period (Erickson, 2011)

Other areas of exploration

Studies assessing serum, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid have identified several metabolic pathways that have association with AD: bile acids, sphingolipids, antioxidants, phospholipids, and amino acids (Snowden, 2017). Other factors like impaired cerebral glucose uptake and insulin resistance and resultant inflammation may play a role in the pathogenesis of AD suggesting that AD is a metabolic disease mediated by brain insulin and insulin-like growth factor resistance (Toledo, 2017; Lazar, 2018). Those with Type 2 Diabetes or pre-diabetes show marked acceleration of brain aging and grey matter atrophy, with the UK Biobank study suggesting that those having pre-diabetes or diabetes were associated with brains that were 0.5 and 2.3 years older than chronological age, respectively (Antal, 2022; Dove, 2024). The extent of cognitive decline in those who were mildly cognitively impaired or who have AD is associated with the degree of glucose metabolism loss, nearly 35% in some brain regions (Weiser, 2016). Those who do not have diabetes or impaired fasting glucose and who have a slightly higher blood glucose level within the normal range still were at risk and experienced brain atrophy, predicted at a rate of approximately 0.06% reduction in total brain volume each year (Walsh, 2018). Some, as a result, are and have been calling AD “Type 3 Diabetes” (de la Monte, 2008).

Microbiome – US National survey estimates that about 57% or 6 in 10 Americans have pro-inflammatory diets with estimates even higher in males, black Americans, younger adults, as well as those with lower income or education (Meadows, 2024). There is increasing evidence to support that gut dysbiosis induces a cascade of inflammation leading to neuro inflammation in what is known as the microbiota–gut–brain axis (Leblhuber, 2021; Ni, 2021; Askarova, 2020; Shemtov, 2022), and may lead to Amyloid beta (Aβ) plaque deposition (a hallmark of AD) (Solanki, 2023). It is believed that the gut microbiome produce inflammatory cytokines as well as certain bacteria in the gut producing bacterial amyloids which may prime the immune system that may lead to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration as well as Aβ formation and deposition in the brain (Leblhuber, 2021;Solanki, 2023) providing a pathway and link between the gut, nutrition and amyloid formation (Pistollato, 2016). One such bacteria that is directly linked to neurodegeneration are Gram-negative bacteria which secrete lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an endotoxin that has been found in greater concentrations in the amyloid plaques of AD patients, and high consumption of saturated fat may increase these bacteria and subsequently increase secretion of LPS (Simão, 2023). A cohort study in older adults evaluating fecal samples found a significant link between gut inflammation and brain pathology with the highest level of gut inflammation found in those with clinical AD. The authors noted that intestinal inflammation may exacerbate the progression toward AD, even at the earliest stages of the disease (Heston, 2023).

Those with AD have a decrease in microbial diversity as well as an abundance of specific bacteria that consistently correlate with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of AD, providing yet another link between the gut and AD (Vogt, 2017).

Factors to numerous to mention can negatively affect the microbiome, but standouts include stress, the Western Diet/ insufficient fiber from plants, and age and in addition, the production of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) from animal product consumption (Simão, 2023). Sleep deprivation also disrupts the gut and is implicated in gut dysbiosis and has been proposed via the gut-brain axis to affect brain function (Lin, 2024; Wankhede, 2025).

Conversely, it has been suggested that the gut microbiome may also exert favorable effects via immune cell and vagus nerve communication with the brain, and that the microbiota–gut–brain axis has a significant impact on neurodegenerative disorders (Simão, 2023). Short chain fatty acids from fiber intake is one example of a protective influence (Marizzoni, 2020) by providing a fuel or energy source for colonic epithelial cells, strengthening the mucosal barrier and keeping pathogenic bacteria that are associated with AD in check via pH level regulation (Simão, 2023).. Fiber will be further explored later in this review.

Controlled trials with administration of either prebiotics or probiotics have been shown to positively modulate brain activity (Liu, 2015; Huynh, 2016). However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials using probiotic and synbiotic (combination of prebiotics and probiotics) supplementation on cognitive function of individuals with dementia found no beneficial effect on cognitive function (Krüger, 2021). The intestinal microbiome has been referred to as ‘the forgotten organ’ and research is rapidly growing and still in its infancy stage (Huynh, 2016). As but one of many examples being explored, polyphenol phytochemicals (plentiful in plant-based diets) are being investigated for their role in supporting the microbiome/gut microbiota.

The Glymphatic System - Another area of investigation is the clearance or removal of waste products in the brain, known as glymphatic flow. The build up of these waste products such as from amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles are hallmarks of AD and several studies suggest impairment of the glymphatic system correlates with the deposition of amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles and that impairment itself may be the pathogenesis of AD (Lemprière, 2022; Buccellato, 2022). As the process of glymphatic drainage is most active during sleep, sleep deprivation has been implicated in negatively affecting glymphatic drainage and increasing amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles (Nedergaard, 2020). Even one night of sleep deprivation can have negative effects on the clearing of β-amyloid, a risk factor for AD (Shokri-Kojori, 2018). Other research involving Microglia (immune cells that also help remove waste in the brain) are compromised in AD patients and were more likely to also be in a pre-inflammatory state and may result in chronic low-grade inflammation in the brain by the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Webers, 2019; Prater, 2023).

Advanced Glycation End Products (AGE’s) – are highly oxidating compounds that promote inflammation and oxidative stress and occur naturally

as part of metabolic processes, through smoking, but also through diet with the top sources being cooked animal protein and fatty foods such as beef, chicken, fish, cheese products, but also heated oils, roasted nuts and seeds (not raw), and less so in bread products (Prasad, 2017).

AGE’s are associated with cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease (AD) and found in areas of the brain such as amyloid plaques and are associated with brain shrinkage (Krautwald, 2010; Srikanth, 2013; Beeri, 2011).

Some research suggests the lower the intake, the less brain atrophy will occur, particularly for grey matter volume (Srikanth, 2013). Vegan diets are lower in AGE’s, though one small study in Europe found levels in the blood to be higher in vegetarians (not vegans), than omnivores (McCarty, 2005; Sebeková, 2001). Ways to reduce AGE include less grilling, baking, and frying and more boiling, poaching, stewing, or steaming (Lotan, 2021). A 16 week randomized controlled trial demonstrated that a low fat vegan diet can significantly reduce AGEP and do so by 79% compared to an omnivorous diet (Kahleova, 2022). Another 16 week randomized controlled cross-over trial demonstrated that a low fat vegan diet also significantly reduced AGEP by 73%, whereas the other diet (Mediterranean) showed no reduction in AGEP at all (Kahleova, 2024).

Ultra-Processed Foods

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are defined as “formulations of ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use, that result from a series of industrial processes (hence ‘ultra-processed’).” (Monteiro, 2019), comprise over 50% of daily caloric intake in the United States (Juul, 2022; Martínez Steele, 2016). These hyper-palatability foods, which are formulated with added fats, sugars, salt, cosmetic additives, industrial substances and flavors meet the criteria for being addictive based on established scientific criteria (Gearhardt, 2022) and have significantly increased risk for many chronic diseases and health conditions (Lane, 2024; Monteiro, 2019), including adverse brain health outcomes. Several studies suggest that those with higher intakes of UPF’s have resulted in greater risk for cognitive decline, dementia, and AD including a systematic review of 5 studies (Li, 2022; Gonçalves, 2023; Claudino, 2024). In the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health, 10,000 participants were followed for about a decade. Those consuming the most processed foods, roughly a quarter of daily calories, had a 28% faster rate of cognitive decline and a 25% faster rate of executive function decline. The authors suggested this major risk was due in part to systemic inflammation from ultra processed foods (Gonçalves, 2023).

Research looking at plant-based diets like the MIND diet, Mediterranean diet, or the DASH diet, found that independent of these dietary patterns, there was a 16% increased risk for cognitive impairment when increasing intake of UPF’s by 10% (Bhave, 2024).

Taking care of gums and teeth to protect for dementia?

Infection by bacteria is implicated in the pathogenesis of dementia and AD (Olsen, 2015; Choi, 2019) with a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies suggesting a 23% and 21% increased risk for cognitive decline and dementia respectively (Asher,2022) . Poor oral health and gum disease leading to periodontal dysbiosis and infection with oral bacteria Porphyromonas gingivalis has been suggested to be associated with increased risk for dementia and AD with this bacteria being found in the brains of AD patients and contributing to neuro-inflammation, and interestingly also prior to onset to dementia (Dominy, 2019; Kamer, 2021) and has been investigated in those with periodontal disease are early as those in their 30’s (Hategan, 2021).

Medications

As previously mentioned, many studies did not control for medications that are associated with brain atrophy (Raji, 2014; Walsh, 2018), but medications can also affect dementia risk. For example, anticholinergic drugs are associated with an increased risk for dementia or cognitive decline with studies estimating up to 23% increase in risk for dementia and a 54% increased risk for drugs with a high level of anticholinergic effect or usage (Fox, 2014; Gray, 2015; Richardson , 2018; Coupland, 2019; Malcher, 2022). And prolonged use for several years has been associated with brain atrophy (Risacher, 2016). These types of medications are routinely prescribed for conditions such as depression, Parkinson’s disease, urinary incontinence, epilepsy, allergies, asthma, high blood pressure, insomnia, dizziness, diarrhea and even as medications for AD itself (Richardson, 2018; Kennedy, 2018), and common medications like Benadryl also contain anticholinergic effects.

Other commonly prescribed drugs such as acid blockers also known as proton pump inhibitors (ie. Prilosec) have been significantly associated with increasing risk for dementia in several studies (Zhang, 2022; Gomm, 2016; Northuis, 2023 ) as is using prescription sleeping pills which may raise the risk of dementia by as much as 79% (Leng, 2023). Other drugs like Benzodiazepines, commonly used as a sedative (Valium, Xanax, Ativan, and Klonopin) also have been suggested to increase risk for AD as well as result in decreased brain volume and increased loss of brain centers involving memory. (Hofe, 2024; Billioti de Gage, 2014). Regular use of opioid pain killers, has also been linked to increasing risk for dementia and reduced scores on cognitive tests, including Tylenol with Codeine, and Robitussin AC. Strong opioid pain killers were associated with reducing brain volume as well as strongly increasing risk for dementia (Lin, 2025).

Water and hydration

Water or fluid intake has also been proposed to affect risk for AD. Chronic under-consumption, or chronic hypohydration, has been suggested to affect risk by continuous release of the hormone angiotensin II, the main hormone controlling body fluid regulation, highlighting the importance of staying hydrated (Thorton, 2016). In the US adult population the prevalence of hypohydration is 37% and in obese individuals 45.7% (Rosinger, 2016).

Environmental chemicals

Fluoride exposure during pregnancy has been consistently linked with neurodevelopmental effects in offspring (Till, 2022). Seafood and fish, are the main contributors (Yu, 2024) to environmental chemicals in pregnant women consuming healthy diets like the Mediterranean and DASH diets (per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)), and why advisories to those who may become pregnant, caution against some species of fish as fish is the leading source of mercury exposure and is associated with cognitive dysfunction and child neurodevelopment (Grandjean, 1997; Masley, 2012; Oken, 2008;Karagas, 2012; Deroma, 2013; Barbone, 2019).

Microplastics, believed to be neurotoxic (Prüst , 2020) have now been identified in human placenta, are another possible area of exploration during pregnancy and child health (Zurub, 2024) and levels have been quantified in seafood, as well as fish (Danopoulos, 2020). Research has also confirmed that microplastics and nano-plastics (MNP) cross the blood-brain barrier and have been deposited into the brain when analyzing cadaver brains (Campen, 2024). It was estimated that the brain harbors approximate 1 spoon worth of MNP’s (Nihart, 2025). Additionally, higher concentrations were found in those who had been diagnosed with dementia, upwards of 3 to 5 times higher. The authors also noted that these plastics are accumulating in the brain at an accelerated pace because when comparing concentrations from cadavers from 2016 to concentrations from cadavers analyzed from 2024, concentrations increased by 50%. The most common plastic found in the brain was polyethylene, which is used for plastic bags and single use water bottles.

(Example of shard-like plastics remnants magnified from brain tissue. Nihart, 2025)

Other research has identified micro/nanoplastics in tea bags that are made from plastic that are released when brewing (Banaei, 2024), to the degree that 1.2 billion particles per milliliter are released when brewing.

Diet (plant-based and omnivore) and Supplements

Diet rather than supplementation should be emphasized, with the exception of Vitamin B12, similar to protective strategies for other chronic diseases. Plant-based nutrients have a positive impact on cognition and hence plant-based diets are recommended for optimal cognitive health (Ding, 2022). Dr. Tanzi a leading neuroscientist at Harvard university believes that “For heart and brain health, there’s nothing better than a plant-based diet.” (Tanzi, 2014). A 2013 International Conference on Nutrition and the Brain concluded with several guidelines including “Vegetables, legumes (beans, peas, and lentils), fruits, and whole grains should replace meats and dairy products as primary staples of the diet” (Barnard, 2014) and several reviews suggested there is mounting evidence in support of plant based diets for reducing or preventing age related cognitive decline and dementia via their neuroprotective effects (Rajaram, 2019; Grant, 2023; Jaqua, 2023), particularly as plant-based diets are recognized in protecting body tissues from oxidative stress and inflammation (Pisttollato, 2014; Ding, 2022), while unhealthy Westernized diets, particularly meat, egg, and high-fat dairy, increase risk (Grant, 2016; Agarwal, 2021), as does high fat diets (Pallebage-Gamarallage, 2016). Short term studies help explain why. For example, in a randomized trial in healthy volunteers, those given a standardized Western breakfast, high in saturated fat and added sugar for just 4 days showed significant changes in hippocampal-dependent learning and memory (Attuquayefio, 2017).

In a preliminary study investigating healthy and less healthy plant-based diets and omnivorous diets, African American adults (but not white adults) showed a protective effect for cognitive decline in those following a healthy plant-based diet while the other dietary groups showed no improvement (Liu, 2022). This highlights the importance of ethnicity but also underscores the difference in following a healthy plant-based diet to an unhealthy one containing unhealthy products like fruit juices, sweets, and refined grains.

In one of the first studies to explore the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, researchers using the DASH Diet with 4 different DASH diet indices found that out of the 4 indices, the one emphasizing high intakes of whole grains, fruits), vegetables, low-fat dairy products, nuts and legumes, along with low intakes of red and processed meats, poultry, fish, and eggs, sweetened beverages, and sodium showed the greatest risk reductions for AD among all indices, a significant 78% reduction (Abbasi, 2025).

A recent study investigating dietary patterns in both Canada and France in over 2800 older people found those following healthy diet patterns characterized by higher intakes of plant-based foods rather than traditional diet patterns or Western diet patterns resulted in higher global cognitive performance. The researchers noted unexpectedly that Omega 3 fatty acids were not associated with healthy diet patterns but rather Western diet patterns despite them being touted as beneficial (Allès, 2019).

Another study also found detriment from the Western style diet. Participants following a mostly plant-based Mediterranean diet but who also included Western style foods (fried food, sweets, refined grains, red meat and processed meat, full-fat dairy) lost some of the cognitive benefit compared to those who didn’t include these foods, to the equivalent of 5.8 years of decline in age cognitively (Agarwal, 2021).

The Women's Health Initiative study in 102,521 postmenopausal women found plant protein intake was associated with reduced mortality from dementia, while fish/shellfish did not show a significant association (Sun, 2021). The study also found that when replacing 2oz per day of nuts in place of dairy products, this significantly lowered dementia mortality.

The Nurses Health Study found that plant protein, rather than animal protein provided better mental health status and mental health scores and only plant protein was significantly associated with having good mental status, which adds support to another study which found plant protein maintained mental health scores in older adults, while red meat showed detrimental changes in mental health scores (Korat, 2024; Matison, 2022).

The Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study, found significant increased risk with red meat or processed meat intake and dementia, accelerated aging in global cognition, verbal memory, and cognitive decline, and additionally, replacing 1 serving per day of nuts and legumes for processed red meat was associated with a 19% lower risk of dementia, 1.37 fewer years of cognitive aging and a 21% lower risk of cognitive decline (Li, 2025).

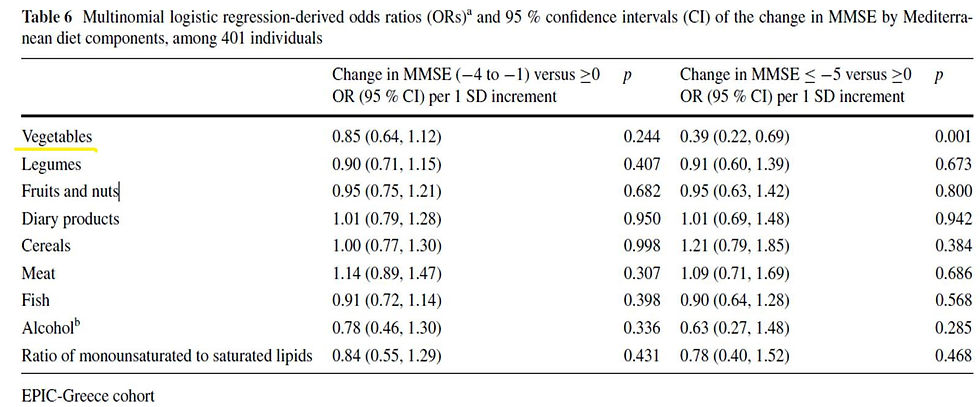

Foods and food groups within a plant based diet have been investigated and are too plentiful to mention. As but one example, nuts are a good plant protein source, are nutrient dense, rich in antioxidants, phytochemicals, and contain neuroprotective components and have been associated with cognitive delay or decline (Ni, 2023). In the UK Biobank study, daily consumption of nuts was suggested to account for a 12% lower risk for all-cause dementia, with the most protective effects coming from unsalted nuts (Bizzozero-Peroni, 2024). Other research investigating nuts found that mixed nuts in particular have been shown in a long term randomized trial to improve brain insulin sensitivity with 60g of mixed nuts daily for a 16 week period (Nijssen, 2023). In the Greek cohort of the EPIC study, out of 9 dietary components, nuts and fruits together were less beneficial, and only vegetable intake was associated with being protective for cognitive decline [Table 6 below] (Trichopoulou, 2014). Another study using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data in over 2600 participants found plant-based diets to score higher in cognitive tests, both in memory and executive function (Ramey, 2022).

Mediterranean diets are generally healthier than Westernized diets and have been suggested to benefit AD or dementia, however most studies that showed benefit were short term (Singh, 2014) and longer term studies have not been shown to have a positive effect for AD or dementia (Glans, 2022). The Direct Plus trial, one of the longest and largest MRI brain studies conducted an 18-month dietary and physical activity intervention in obese adults found that compared to the group following normal dietary guidelines, those following a Mediterranean diet or a Mediterranean diet particularly high in polyphenols, low in red meat and high in plant foods resulted in significantly reduced brain atrophy (50%) with improved insulin resistance and glycemic control (HbA1c levels) being the strongest factor attributed to the change (Kaplan, 2022; Pachter, 2024).

In a multi-site randomized controlled trial, a whole foods plant-based diet along with other lifestyle modifications for 20 weeks resulted in a significant improvement in cognition and function in early stage AD or mild cognitively impaired participants. Additionally, improvement in the gut microbiome occurred, with less organisms known to increase AD risk, and more organisms known to reduce risk (Ornish, 2024).

Brain health supplements

Brain health supplements are widely promoted and expected global sales for 2026 are to top $11.3 billion (KBV Research, 2021). Supplements in studies for AD or dementia or cognitive decline have largely been without success or significant benefit, including Vitamin E, D, B vitamins, calcium, copper, zinc, selenium and mixed to low evidenced of benefit for beta-carotene and Vitamin C (Rutjes, 2018; Kryscio, 2017). The World Health Organization advises against the use of brain health supplements for cognitive decline or dementia (WHO, 2019). These include Vitamins B and E, polyunsaturated fatty acids and multi-complex supplementation which should not be recommended to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and/or dementia.

In 2019, the FDA cracked down on 17 supplement companies who had false claims for brain health on their labels (FDA, 2019) including vitamins, minerals, Omega 3, herbal products, as well as "nootropics", supplements purported to benefit cognitive function.

And in 2016, CVS drug, who touted an algae DHA supplement that prevents dementia was successfully sued for this deceptive claim and the FDA forcing removal of the claim.

Supplements can also be harmful. For example, Resveratrol supplements in two randomized controlled trials caused a significant acceleration (triple compared to control groups) of brain volume loss in both studies (Turner, 2015; Gu, 2021). In another study using Vitamin E in AD patients, the second group, "non-respondents", consisted of patients in which vitamin E was not effective in preventing oxidative stress. In these patients, cognition decreased sharply, to levels even lower than those of patients taking placebo. Based on these findings, it appears that vitamin E lowers oxidative stress in some AD patients and maintains cognitive status, however, in those in which vitamin E does not prevent oxidative stress, it is detrimental in terms of cognition. The authors noted that supplementation of AD patients with vitamin E cannot be recommended without determination of its antioxidant effect in each patient (Lloret, 2009).

“There is zero evidence from any reasonably rigorous study that any supplement or dietary aid has any benefit on cognitive function or decline in late life,” says Dr. David Knopman at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota (Knopman, 2019), though a recent study suggested some benefit with multi-vitamin supplements with improved cognition and memory but it is not known whether those nutrients could of been deficient as part of a poor diet (Baker, 2022; Yeung, 2023).

Fish Oil Supplements. Despite no federal qualified health claim for fish oil supplements for brain health, a recent review of fish oil supplements found that 37.5% use a claim for brain health. Additionally, there is no requirement for supplement companies to disclose potential risks, for example, the increased risk for atrial fibrillation (Assadourian, 2025). Other concerns about fish oil supplements in particular include adding insult to significant depletion and overfishing of fish stocks and increasing concern regarding sustainability. Pollutants are also a concern. A 2013 study examining children’s fish oil supplements found that every sample contained levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (Ashley, 2013).

Atrial fibrillation

A meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled studies with long term use of Omega 3 fish oil supplements was also found to increase risk of atrial fibrillation with increasing doses further increasing risk (Gencer, 2021). Another study (UK Biobank) also confirmed this in healthy populations with no cardiovascular disease in which regular use of fish oil supplements resulting in no primary prevention benefit and instead an increased risk for atrial fibrillation and also stroke (Chen, 2024). The American Heart Association highlights the heart-brain axis in their Scientific Statement that atrial fibrillation may compromise cerebral blood flow potentially damaging small blood vessels in the brain and creating microhemorrhages instrumental to cognitive function (Testai, 2024). A meta-analysis suggested a twice-fold increase risk for dementia in those with AF (Kwok, 2011) while another suggested a 1.4 to 2.2 fold increase risk for dementia or cognitive impairment and increases in white matter hyperintensities and decreased cerebral perfusion and cerebral volume (Koh, 2022; Papanastasiou, 2021).

Plant-based diets, on the other hand, may reduce many of the risk factors associated with atrial fibrillation including hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and hyperthyroidism, as well as reduce inflammation which is linked to atrial fibrillation (Storz, 2020; Leszto, 2024).

Calcium: An Example.

Calcium intake is yet another factor that is rarely if ever controlled for, particularly calcium supplements. In elderly women with evidence of cerebrovascular disease who were followed for 5 years, calcium supplements doubled the risk for developing dementia compared to those who did not supplement (Kern, 2016). In women with a previous history of stroke, calcium supplements increased the risk 7-fold for developing dementia compared to those who did not supplement. Women without history of stroke did not have an increased risk from supplements (Kern, 2016). Another study in both elderly women and men showed increased brain lesions with calcium supplement use compared to those who did not supplement (Payne, 2014). Another study in elderly women and men found combined dietary and supplement calcium increased brain lesion volume (Payne, 2008). Excess calcium could possibly play a role in its relationship to calcified carotid plaque and may constrict blood vessels within the brain which could result in lesions.

Vitamin D

One study examined concentrations of Vitamin D (25(OH)D3 ) in four regions of the brain finding that higher levels were associated with better cognitive function prior to death but no association post-mortem with any dementia-related neurological disorder including AD (Shea, 2022). Vitamin D supplementation has been associated with significantly longer dementia-free survival and lower dementia incidence, though study limitations included not recording baseline and follow up Vitamin D levels nor dose or duration of supplementation (Ghahremani, 2023). In the UK Biobank study, those with either Vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency consistently showed a 10 – 15% or 19 - 25% increased risk for dementia (Chen, 2024). Low levels of Vitamin D status at the very deficient level (<25 nmol/L or 7-28 nmol/L) have been associated with cognitive decline and AD, however not in all studies (Olsson, 2017; Duchaine, 2020), with some suggesting high levels actually increased risk for dementia or AD (Duchaine, 2020), and with mixed to poor results in clinical trials (Autier, 2014), but is a good reminder to ensure adequate (but not excessive) intake, particularly by sun exposure (or even exposing mushrooms to sunlight), as chronic use of Vitamin D supplements carry other risks such as excessive calcium buildup in the body and possibly tissue damage (Razzaque, 2018; Annweile 2016; Anjum, 2018; Sultan, 2020; Farghali, 2020).

Vegetarian and Vegan populations

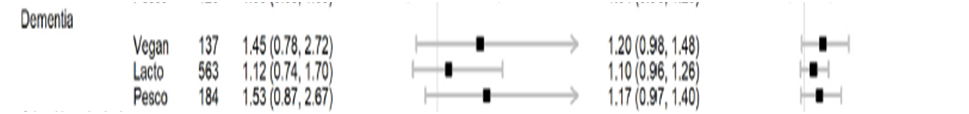

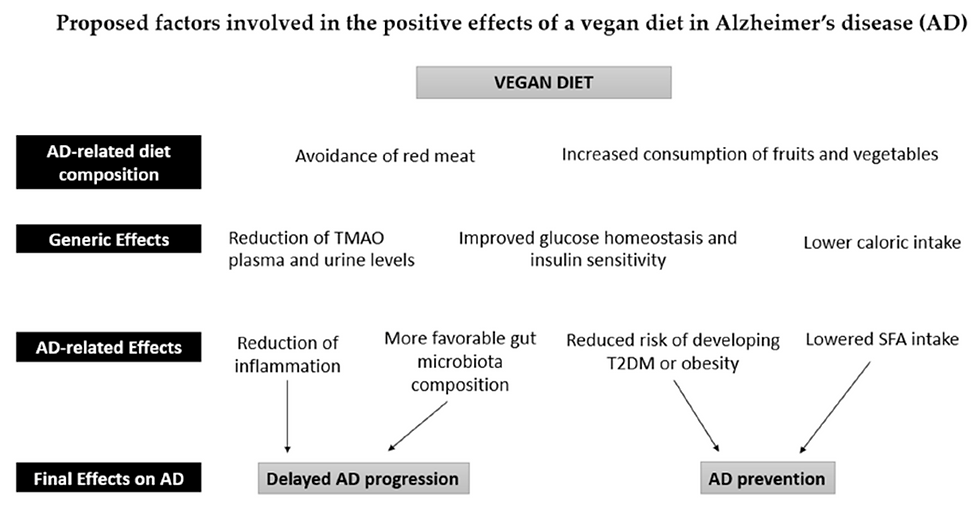

Few studies have assessed dementia and AD in these population groups.